BY DR. KEN CAMACHO

Note: This script was used for a sermon delivered at Revolution Annapolis in March 2017

This week, we are continuing a new series called “What If He MEANT It?” by once again looking at some of the more difficult and radical words of Jesus–words that we often tend to “water down” or rationalize–and challenging ourselves to consider the possibility that Jesus actually meant just what He said…even if what He said can be difficult to accept.

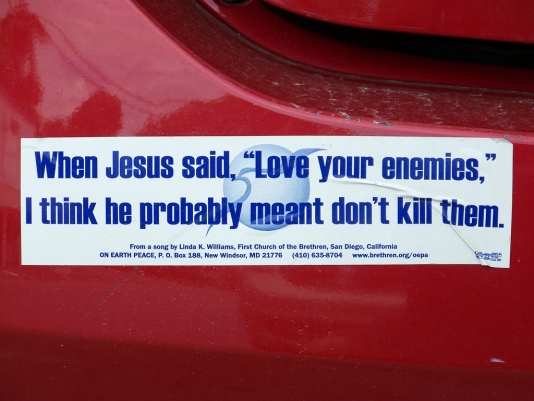

Last week, I started the series off by looking at two statements from Jesus’s “Sermon on the Mount,” which is one of the most complete accounts we have of an example Jesus’s teaching. Specifically, we looked at Jesus’s challenge in that sermon to “turn the other cheek” when we suffer an attack, as well as his instruction to “love our enemies.” We concluded that these instructions, although extremely difficult for us, are nonetheless intended to push us towards a love that is more like God’s love for us. By “turning the other cheek,” we are able to act out our trust in God’s control and in His justice, and by “loving our enemies,” we are able to imitate God’s patient and forgiving love for us. After all, we have also been His enemies–we have all disobeyed Him, and we have each certainly been guilty of standing in the way of the work God is doing in our lives and in our world–and nonetheless, God has been patient with us, He has loved us, and He has invited us, over and over again, to come alongside Him in His mission to restore the world to its designed purpose. Jesus’s words, then, are certainly challenging–but they are also reminders of who God is, and how God loves, and when we choose to accept them, and even follow them, we are, as the verses we quoted last week insist, being “sons and daughters of God.”

It would appear that 1st century wardrobe options were limited.

This week, we are going to focus on a single verse, also from the Sermon on the Mount and also recorded in the fifth chapter of the book of Matthew in the Bible, which presents an almost unimaginable challenge. It comes immediately after the verses we studied last week, and it goes like this:

Matthew 5:43-48:

“You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be sons of your Father who is in heaven. For he makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the just and on the unjust. For if you love those who love you, what reward do you have? Do not even the tax collectors do the same? And if you greet only your brothers, what more are you doing than others? Do not even the Gentiles do the same? You therefore must be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect.”

Sadly, after spending the last two weeks doing research for this sermon, I am afraid I have to tell you the truth: that last sentence is not a typo. There is no way around this one: not by putting it in “historical context;” not by looking for a loophole in the verses that come before or after it; not even by looking at the original Greek, or even reverse-translating things into Aramaic or Hebrew. There are only those five words, and they mean just what they seem to mean: You therefore must be perfect. Perfect. As in, “without error.” And “You,” as in…you. You therefore must be perfect.

But what does that mean?

Well, I think we can start by crossing off a few of the things we might wish it means. One of the purposes of this series is to push back at the ways we tend to minimize what Jesus says, and so I think it is a critical step to put our excuses out there, as clearly as we can, so we can hopefully see the ways we are all guilty of misinterpreting Jesus, before we get into how we can or even should interpret him.

So, I’ll go first: when I hear Jesus say, “be perfect,” here’s what I immediately think: I think what he’s saying is do your best.

Now, I am 35 years old. I was born in the early 1980s, and I graduated high school in the year 2000. This means that, in terms of the ways we often talk about “generations,” I fall right into a gray area between “Generation X” and the “Millennials” we are all always hearing about. So, maybe I’m not completely connected to all of those “Millennial” stereotypes, but I can at least see them from where I’m standing. And one of the most irritating knocks on Millennials, I think, is this idea that folks from this generation were raised in the age of “participation trophies.”

I literally had dozens of these.

I think the version of this complaint we see in popular media–the same version that showed up in a million memes during the 2016 election cycle–is pretty horrifically unfair. It generally posits some version of the following argument: because Millennials were raised in a touchy-feely, hippie-nonsense age of believing “everyone is a winner,” they are incapable of handling criticism or the so-called ‘harsh realities’ of adult life. Instead, they are arrogant and full of themselves, and they just can’t understand it when things don’t go their way. Now, I think this criticism is pretty off-the-mark, and even downright offensive: I don’t think getting a participation trophy when I was in Little League has ruined my ability to understand the harsh realities of life. In fact, I’m pretty sure that even when I was 8, I understood that the tiny participation trophy I got for playing right field, and the freakin’ boss MVP trophy the kid who played short stop and batted .750 got at the end of the year picnic were not equal, and I definitely knew then that nobody, including me and even my parents, believed that kid–Randy was his name–and I were equal.

But I did get another message from that trophy, which is one I value and one I want my kids to receive one day, too: just because Randy was better than me at baseball didn’t mean that I was worthless. That little trophy was meaningful because it encouraged me to keep playing, and not to give up, which, I think, is a pretty excellent message for kids. And as far as I’m concerned, if my city or my community is going to be filled up 20- and 30-somethings who understand how to be motivated and included, I am excited about that. So, way to go Millennials! If you any of you are out there this morning, good on you! I’m glad you’re here, and I hope you stay!

Studies suggest that at least 42% of MVP trophy recipients in the 1990s were named “Randy”

How does this relate to Jesus? I think one of the ways I misread Jesus’s instruction to “be perfect” is that I get confused about the difference between doing my best and thinking my best makes me an MVP. So, I tend to want to minimize Jesus’s challenging words–I tend to want to settle–by thinking that when he says “be perfect,” what he means is, “don’t worry; we’re not even having ‘MVPs’ this season–doing your best; trying to catch the occasional fly ball in right field, or batting .222, is all we are expecting.” And because I get this part of things wrong, it does the opposite of what that participation trophy was supposed to do when I was in Little League: it makes me not want to keep trying; it makes me content to simply stay right here, right where I’m at, more or less doing my best to be a decent human being, but still leaving a ton of room for slip ups, for doing what I want to do, regardless of whether or not it’s what God has called me to do. So, I try not to yell at my kids; I try to think of something nice to do for my wife from time to time; I try to call my friends, and check in with my mom and dad, from time to time; I try to be nice to my coworkers when I feel like it; and I try to be generous with my money whenever I have a few dollars in my pocket…but when I mess up? Well, oh well–nobody’s perfect.

And of course, that’s exactly the problem with seeing ‘my best’ as ‘good enough,’ at least as someone who identifies as a follower of Jesus: I am follower of Jesus, which means that I believe somebody WAS perfect. In fact, it’s at the root of my entire belief system! Jesus won the giant MVP trophy! Jesus is “Randy,” the all-star shortstop! So how in the world have I–how in the world have we--slipped into a state of living, a state of belief, where we think that participation in holiness, participation in Godliness, can count as good enough?

Now that’s a question I think we can actually answer, but I don’t think we’re going to like what we find. My claim this morning is that we fall into this trap of believing that an honest effort is good enough to count as perfect because we don’t think Jesus is really anything like us at all. We fail–systematically and personally and completely–to hold on to what is perhaps the most important and beautiful thing about the guy who is supposedly at the very center of our religion and our very lives: that He is one of us.

There are two parts, I think, to this mistake, two reasons we trick ourselves into believing that Jesus isn’t on our “level”. The first is that we don’t want to believe that Jesus faced the same problems we face.

Now, there are plenty of well-known verses in the Bible that contradict this belief, and they are a great place to start: in the book of Hebrews, the author writes, “For because he himself has suffered when tempted, he is able to help those who are being tempted,” and then later: “For we do not have a high priest (meaning Jesus) who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but one who in every respect has been tempted as we are, yet was without sin.” Similarly, we have Jesus’s own insistence on his humanity, both to his disciples in private and to the Roman and Jewish authorities who repeatedly interrogated him. We see it in Jesus’s actual birth and life, as well as in his submission to the ritual of baptism when he meets John the Baptist: whatever else–whoever else–Jesus might be, the Bible goes to great lengths to show us that he is definitely a real-life human being.

But, at least for me, the doubts I hold to, which complicate my belief that Jesus knows what I’m going through, are far less rational than all that. If I’m honest, they aren’t actually reasonable objections at all: if you forced me to admit, do I think Jesus understands my own life and difficulties? I would say “yes.” But I don’t live like it because I hate that Jesus makes it look so easy. I hate how petty that sounds, but maybe it rings true for you this morning, too: I don’t want to believe Jesus lived a human life because I know I’m constantly failing to live up to the standard of perfection, and when I think about Jesus pulling that trick off, I get mad. I get, frankly, jealous because I know I’m not measuring up, and the worst part is, I know that I’m trying. So, it’s easier for me to just throw in the towel.

Speaking of sports, one of the things that I most hated about playing sports when I was growing up was my ever-growing surety that everyone was lying to me about the importance of practice.

You should ALWAYS wear Game Day gear while chasing airballs into your neighbor’s bushes.

For as long as I could remember, every adult in my life kept saying to me, “if you want to get better at catching a ball or making a free throw, you have to practice.” And so I would: I would practice shooting free throws in my driveway for hours. But you know what? I couldn’t practice my way out of being short and unathletic. I tried, and honestly, I got pretty good at free throws…but I still couldn’t compete, and the more I played sports, the more I started to get super mad at the people who were better than me. And you know what made me maddest of all? I knew I practiced more than them. Way more. But they had something I didn’t have: they were actually talented; like, God-given, #blessed talented. And I wasn’t. So I didn’t think comparing me to them was “fair.” And right there–right in that soft spot–bitterness grew in my heart. I don’t like when Jesus, of all people, tells me to be “perfect” because I want to believe that Jesus was talented when it came to perfection. Because it lets me off the hook. And the challenge of those verses in Hebrews–the things about them that should hit me, and my pride, like a sledgehammer?–is that I’m wrong. Jesus wasn’t supernatural. He lived a life, just like me. AND–not “but,” but AND–he did it perfectly. So, if I’ve been hoping to be graded on a curve–if I was hoping for a “participation trophy”–I’m about to have some tough luck. Why do I struggle to believe that Jesus was “one of us,” that he was really and truly like me? Because if that’s true…the only conclusion I feel like I can reach is that I’m not good enough.

The second part of our resistance to believing that Jesus was–is–”one of us” stems from the first. It is this: we don’t want to believe that we are really being held to the same standard as him. But again: we are wrong.

This time, I think the problem we have comes from a real confusion about what it means to “be perfect.” This time, let’s take a step away from the world of sports and head into the classroom. You guys remember those, right? Boring lectures, worksheets, and, from time to time, end of chapter tests? Let’s think back to those test: what would it mean to get a “perfect” grade? To earn an “A,” or 100%? Well, it would mean remembering all the answers. Being “perfect” isn’t about doing something superhuman–it’s not about having more than what is expected of you…it’s about fully living up to an expectation for you. For you. It’s about being 100% of what you are intended to be.

But what are we “intended” to be?

When I was a high school teacher, I shared a classroom with my friend Isaac, who was a Bible teacher. So, I ended up getting to sit in on hundreds of Bible classes over the years. One of Isaac’s “trademark” lessons was a unit he would do every spring on the imago Dei, which is Latin for “the image of God.” It’s a long-standing belief of fundamental Christianity, and it is pulled from the very first book in your Bible, the book of Genesis. In Genesis, chapter 1, God describes the creation of human beings in these terms: He says (to Himself, interestingly),

Genesis 1:26-28

26 And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth. 27 So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.

Now, the key in these verses, as far as Isaac’s class was concerned, was this issue of “image”: the Bible says that human beings aren’t just the invention of God, they–we–are His image-bearers. That means that we look like God looks; we are copies, in a sense, of Him. Now, the point Isaac was trying to get at by looking at these verses was to challenge something that students, and, in fact, most people, say all the time: we say, when we do bad things, or when we feel drawn towards sin, or being selfish, or being cruel, or being greedy that these feelings are just “human nature.” And Isaac’s point is that we are exactly wrong: sin isn’t in our “human” nature at all–because we are image-bearers of God! Rather, the way we ought to think about sin is like this: when the Bible says sin entered the world and we “Fell” into it…it means what it says! The problem isn’t that sin is in our “human nature”…it’s that we aren’t living as fully human. Some translations of the Bible use the term “sin nature” as a way of referring to our nature after our desires shifted from a desire to be like God made us to be–a “human” nature–to a desire to be what WE want to be–a “sin” nature.” The point is that when we are drawn towards sin, when we are drawn towards selfishness, or greed, we are being pulled away from what we were designed to be. We were made in the image of God…but all too often, we fail to hold that image up.

Here’s where I’m hoping to go with all of this: when Jesus says, in Matthew 5, that we must be perfect, I know there’s a part of each and every one of us that recoils a bit–or, at least, there really should be! And maybe, there’s another part of us that tries to push back: maybe by saying, “I don’t know; maybe Jesus is just saying that we should work really hard, and do our best, and in the end, that will be good enough.” But then came Jesus: by showing us what perfect looks like, he becomes the “MVP,” the kid on your team when you were young who exposed that “your best” wasn’t, ultimately, good enough.

Or, maybe, you push back against what the Bible says, against its charge to “be perfect,” by believing that Jesus Himself is unrealistic: either he doesn’t really understand your struggle; or maybe he kind of “cheated, by also being God; or maybe the Bible is unrealistic to expect a human being to “be perfect” anyway, because our nature is to sin…but then came Jesus: a guy who lived a life with the same struggles as you; who knew what it was to be tempted, but in the midst of temptation, succeeded in living up to the standard of “humanity” that has always been God’s hope and intention for us as beings made in God’s image.

And so, here we are: we have to admit that

- Perfect means “perfect”

- Perfection is a reasonable expectation

- We can’t do it

And that last realization–that we just can’t meet the expectation God has for us, that we can’t be “perfect”–is devastating. I know why we run from it; I know why I do, at least. I don’t want to look in a mirror; I don’t want to accept that I come up short, over and over and over and over, day after day…and that I know I will come up short again tomorrow, if it’s up to me: in my marriage; in my parenting; in my friendships; in my work; in my faith. I have to admit–I have to confess-that I’m not up to “perfect.” But then came Jesus. And with him, two promises that revolve around each other like twin suns at the gravitational center of my faith:

- The first of those promises is this: If I’m willing to follow him, He will be my advocate. His perfection, his essential humanity, will be “added unto me,” is the way the Bible frequently puts it; in Christian theology, the word people usually use is “imputation.” But regardless of your terminology, the point the words recognize is this one: Jesus is on your team. He wants you to benefit from his perfection; he wants what that perfection enables, which is a restoration of what it means to even be human, to be offered to you, too. It doesn’t have to continue to matter that you have been imperfect in the past because Jesus isn’t in competition with you; he loves you, he knows you, he understands how this is difficult for you, and he is on your side.

- The second promise is this: If I am willing to follow him, He will fix me. He will repair me, or restore me, back to what I was made to be. I have not been perfect, God knows…but I can be perfected. The first 20 minutes of our talk this morning can feel devastating: the point was to recognize-to realize-that we are out of excuses for why we should be LESS than God made us to be. But maybe we don’t need to be devastated by that realization. Because there is a better side to what I just said: We are out of excuses for why we should be LESS than God made us to be. What we are isn’t good enough because what we are isn’t good enough: we are meant to be more. This isn’t something I “kind of” believe–it is the beating heart of the entire Gospel of Jesus Christ, it is the core Truth of the entirety of the Christian faith: We can be what we were made to be.

The apostle Paul, whose influence on the first 100 years of the Christian church is unparalleled, puts it this way:

2 Corinthians 5:17-21

Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation. The old has passed away; behold, the new has come. All this is from God, who through Christ reconciled us to himself and gave us the ministry of reconciliation; that is, in Christ God was reconciling the world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them, and entrusting to us the message of reconciliation. Therefore, we are ambassadors for Christ, God making his appeal through us. We implore you on behalf of Christ, be reconciled to God. For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God.

Paul is explaining to the early church just how big of a deal what Christ did is for us: by being perfect, Jesus wasn’t showing off; by dying on the cross, he wasn’t just being a “martyr”…in all things, he was “reconciling us to God.” He has shared his perfection with those who follow him, and he has initiated the “ongoing work” of making those same followers into his image. Paul says, “in him we might become the righteousness of God,” and we do this by first admitting that we aren’t going to hit the target of perfection on our own, and then following step-by-step in the footprints of the one guy who ever lived and HIT IT. It’s truly not about how much we have messed up in the past–it’s not about carrying guilt for all the times we didn’t measure up–just like in the metaphor of the classroom or the test, the point is learning everything we are meant to know. It’s about getting to 100%; not having always been there.

There is an interesting translation issue at work in our central verse this morning that I think has the potential to give hands and feet, so to speak, to what Jesus is doing in the lives of those who follow him. It actually comes from the book of Luke, where Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount is recounted from the perspective of another listener. In Luke’s account of the sermon, the word Jesus is using when he says “perfect” is better translated “merciful.” So, Luke 6:36 records the moment like this:

Luke 6:36

“Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful.”

Mercy is a pretty “churchy” word, I know, so we often use it without taking the time to explain precisely what it means. But this morning, it seems like a good idea to dig for a definition. Here’s how Merriam-Webster sums it up: “compassion or forgiveness shown toward someone whom it is within one’s power to punish or harm.” When I was a kid, my Sunday school teacher helped me remember it this way: she said, “mercy starts with ‘m,’ which is only one letter away from ‘n’, so you can remember it like this: mercy is NOT getting what you deserve.” Okay, that might be a little too clunky to be helpful for you all, but it has long worked for me: mercy is NOT getting what you deserve.

So, what does Jesus mean, when he tells us to be “merciful,” and if we combine the two records of his words, to be “merciful perfectly”? Well, I think we can go back to the verses from just before this exhortation, which we talked about last week: being “merciful” means loving others-loving our enemies-in the same way that God loves us. And how does God love us? He loves us enough to make a way for our relationship to be repaired. He loves us in a way that not only forgives, but advocates; He loves us in a way that changes us into being more like how we were designed to be. He loves us in a way that perfects. Sure, expecting us to love others like that is asking a lot…but if we’re following in the footsteps of Jesus, He will lead us there. Remember that second promise, the second of those “twin suns” circling one another at the center of the system of Christian faith: God is doing this work. In a letter to the 1st century Christian churches in the city of Philippi, the apostle Paul puts it this way:

Philippians 1:6

“And I am sure of this, that he who began a good work in you will bring it to completion at the day of Jesus Christ.”

There may be no sweeter verse in the Bible, as far as I am concerned: “I am sure of this: that he who began a good work in you will bring it to completion.” Sure, you are not perfect; sure, your best is not good enough; you know how far you are from earning a 100%…but if you are following Jesus, you are on your way there. The “good work” has begun…and it is God’s promise to us that He will “bring it to completion.”

So, as we wrap up today, I want all of us to leave with two very specific questions that we can wrestle with in the week ahead. The first is this:

Do you believe it?

Do you believe that, first of all, perfection matters to God? Are you still convinced that “doing your best” is good enough? If so, is it possible that your reasons for believing that look a lot like mine, particularly that I struggle to believe that it’s fair to compare me to Jesus? If that is where you are this morning, can I ask you to think about something this week? Think about this question: if the ‘line’ for ‘good enough’ isn’t at ‘perfect’…where is it? At the end of the day, which belief is harder to accept: that God expects perfection…or that he doesn’t?

Secondly, do you believe that perfection is possible for you? If your answer to that is ‘yes,’ that’s okay! I’m not going to shout you down, or tell you that you are wrong–it’s okay to hold that belief. But I will challenge you not to hold it in the abstract. So, this week, if you’re not sure that perfection is impossible, give it a shot: for a week, or even for a day, strive intentionally for just one aspect of perfection: strive to be unfailingly kind. Do this towards everyone: friends, family, co-workers, strangers, politicians–be unfailingly kind. Hey, if you’re right–if this is possible for you–then the world is a better place with you being kind to everyone! But if it’s not possible–if even your best effort isn’t good enough–I want to challenge you to come back to this spot: if perfection matters, but you can’t do it, what are you going to do? And, if I might be so bold, can I challenge you, just one more time? Is there room inside of you to consider that perhaps “perfection” isn’t something you start with–you come into this life with a full and perfect cup, and you spend your life trying not to spill any of it–but instead something you are brought to? In Jesus’s words, what He offers is not a handful of patches for your leaky cup but living water, overflowing in abundance. Jesus is trying to fill you up…would you consider letting him?

The second big question I want you to wrestle with this week is this one:

Are you moving?

Gandalf the Grey shows up precisely when he means to.

One of my wife, Meredith’s, least favorite things in movies or TV shows is when an urgent situation arises, and a character spends precious seconds talking about it or explaining it before they actually act. A classic example of this, for her, is the scene in the first Lord of the Rings movie when the “fellowship” is in the Mines of Moria, and the goblins have them surrounded, but then they begin to hear this deep, rumbling noise, and all the goblins and orcs scatter away. There’s this moment, after the fellowship is alone, where Gandalf, the wizard, closes his eyes, and listens carefully, and then he begins to see the red light coming from the other end of the giant hall, and he explains that the monster they are about to encounter is a “Balrog;” shadow wreathed in flame; an enemy far too dangerous for them…and then, after all that talking, he shouts “RUN!” When Meredith and I rewatch that movie, she loses it, every time; she shouts at me (or maybe it’s at the TV?), “what are you doing?! SHUT UP AND RUN ALREADY!!” It’s that ten-second pause, when Gandalf is talking, that just kills her: “if you know it’s a giant monster, don’t just talk about it…get moving!”

The last challenge for you this morning comes out of precisely this same anxiety: are you moving? God has set a goal, an expectation, a target for you: it is perfection. AND he has promised that, if you will follow him and trust him, he will remake you into that goal. He will bring to completion the work he has begun in you! But are you moving? Are you taking steps in the footprints Jesus leaves behind? Specifically, if you know your goal is to “be merciful, as your Father is merciful,” or to love your enemies as your Father loves you, what are you doing to pursue it? How are you seeking to know God’s love more? Are you looking for it in your own life? Are you reading about it, praying about it, keeping notes on it, when you see it at work in your life, or in the lives of other people? Are you working to love like God loves? Are you seeking out chances to show mercy, are you racing to ask for forgiveness, and to forgive others, as fast as you can? Are you setting an expectation for yourself, to work to bring God’s kingdom, his love, his Truth, his hope, to bear here, in your life, right now?

If not…what are you waiting for?

What if that same fear that kept you from wanting to looking in the metaphorical mirror earlier–that fear that what you would find wouldn’t be perfect–what if that fear could be replaced by an eagerness to look in the mirror, in order to see what God has done in your life?

One of the greatest comforts and securities I have in my life and in my faith comes from very intentionally looking backwards: although, in the day-to-day experience of my life, I often fail to see God at work in me, or the ways that following Jesus is transforming the person I am into the person I was made to be, when I look backwards–when I look at my life 5 years ago, or 10 years ago, or 15 years ago–it is amazing to me what God has done. I am not the person I used to be, and it’s not because I worked really hard to be better…it’s because God is at work in me. When I say that you need to go, that you need to run; that you need to stop waiting; I’m not saying that you can go make yourself perfect. But I am saying that if you run towards the model of Jesus–if you seek, with all of your mind and heart and soul, to know Him more, and to care about the things he cares about, and to do the kinds of things he spent his whole life doing…God will make you unrecognizable to yourself. But recognizable–perfectly recognizable–to Him.

Let’s pray.